Fusion Inhibitors

Reviewed by: HU Medical Review Board | Last reviewed: May 2025 | Last updated: May 2025

Fusion inhibitors are a class of drugs used to suppress HIV in the body. When fusion inhibitors are used in combination with other HIV-fighting medications, the treatment regimen is referred to as antiretroviral therapy (ART).1

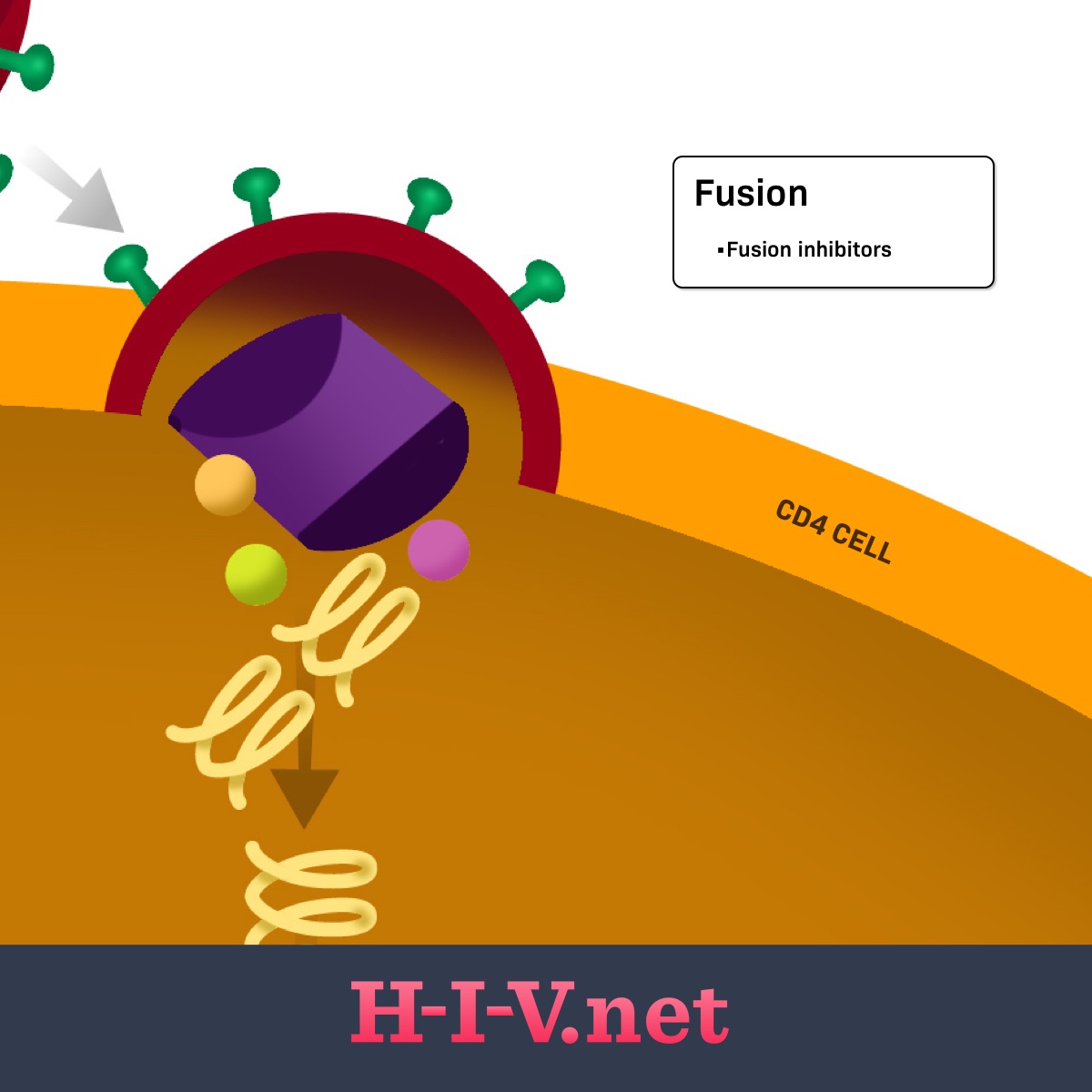

HIV needs to enter human host cells, called CD4 cells or T cells, to replicate. To enter into these cells, HIV needs to bind to the host cell surface and then fuse with the host cell to get inside. Fusion inhibitors block this step in the process, preventing HIV from getting into its target cell and replicating.1

HIV life cycle

Viruses, like HIV, need human host cells to replicate. They cannot multiply on their own without human cells. When HIV particles, called virions, enter the body after a transmission event, the next main steps of the HIV lifecycle are as follows:2

- Binding

- Fusion

- Reverse transcription

- Integration

- Replication

- Assembly

- Budding

Figure 1. Fusion inhibitors target fusion in the HIV life cycle

The HIV virions have proteins on the outside that recognize receptors on CD4 cells. Once a virion finds a CD4 cell, its outside proteins can bind to the CD4 cell receptor and link the CD4 cell and virion together (step 1: binding). For the virus to fully bind and fuse with the CD4 cell and get inside the cell to continue replication (step 2: fusion), other receptors on the CD4 cell surface may get involved. These additional receptors on the host cell include the CCR5 or CXCR4 receptors. The HIV surface receptors involved in the first two steps are called gp120 and gp41. Any of these receptors on the CD4 cell or HIV itself may be targets for HIV medicines.2

Once inside the cell, the virion disassembles itself so that it can begin the replication process. The next three steps represent the replication process of the virus’s genetic material. The last two steps of the process involve HIV reassembling itself into new, mature virions that can be released from the CD4 cell and enter the bloodstream, where they can go on to infect new cells.2

How do fusion inhibitors work?

Fusion inhibitors bind to the gp41 protein on the outside of the virus. Gp41 is involved in the physical merging of the outside of the virus and CD4 cells, allowing HIV to get inside the host cell. This blending and absorption of the virus is called fusion. By blocking gp41, the main protein involved in this process, the fusion process is prevented or inhibited. This is where this class of medications gets its name.3

Other medicines that can be used to block the physical connection between HIV and CD4 cells are called CCR5 inhibitors or post-attachment inhibitors. However, fusion inhibitors are different in that they block the step after binding. When using a fusion inhibitor, an HIV virion is allowed to physically link to a CD4 cell, but it cannot fuse with the host cell and get inside.1,3

Examples of fusion inhibitors

Enfuvirtide (Fuzeon®) is an example of a fusion inhibitor to treat HIV. However, as of February 2025, it has been discontinued in the United States.1,3-5

What are the possible side effects of fusion inhibitors?

The most common side effects of fusion inhibitors include:4

- Injection site reactions

- Diarrhea

- Nausea, stomach pain

- Tiredness

- Weight loss, decreased appetite

- Sinus problems

- Cough

- Herpes simplex

- Pancreas problems

- Pain in arms and legs

- Pneumonia

- Pain and numbness in feet or legs

- Flu-like symptoms

- Infected hair follicle

- Dry mouth

- Eye infection

These are not all the possible side effects of fusion inhibitors. Talk to your doctor about what to expect when taking these drugs. You also should call your doctor if you have any changes that concern you when taking fusion inhibitors.

Other things to know

Before starting treatment with fusion inhibitors, tell your doctor if you:4

- Have bleeding problems

- Have or have had lung problems

- Have a low CD4 count

- Smoke or use intravenous (IV) street drugs

There is not enough data to know if fusion inhibitors are safe to take while pregnant. Before starting treatment with fusion inhibitors, tell your doctor if you are pregnant, planning to become pregnant, or breastfeeding. They can help you decide if they are right for you.4

Fusion inhibitors may cause a condition called immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS). IRIS occurs when a person's immune system gets stronger after being weak and responds aggressively to previously hidden infections. This heightened response may make the person fighting the infection feel worse.4

Before beginning treatment for HIV, tell your doctor about all your health conditions and any other drugs, vitamins, or supplements you are taking. This includes over-the-counter drugs.