The Life Cycle of HIV

Reviewed by: HU Medical Review Board | Last reviewed: September 2024 | Last updated: September 2024

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a virus that attacks the body’s immune system. HIV infection begins with an acute stage (intense reaction) and may progress to chronic (ongoing). At its most advanced stage, HIV can cause acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). There are now treatments available to prevent the progression of the virus.1-3

HIV targets the body’s CD4 cells. These cells are also called T-cells or lymphocytes. Lymphocytes work to fight infection. HIV destroys CD4 cells, which lowers the immune system’s ability to protect itself. The person with HIV then becomes more at risk of serious illnesses and cancers.1-4

Start a Forum

How is HIV transmitted?

HIV passes from 1 person to another through certain body fluids. The infected fluid passes through mucous membranes to reach the bloodstream. Blood, semen, vaginal fluids, and breast milk can all contain HIV. The most common methods of transmitting HIV include:1

- Unprotected anal or vaginal sexual intercourse

- Sharing of needles

- Childbirth

- Breastfeeding

Tears, saliva, and sweat cannot transmit HIV. Kissing cannot usually transmit HIV, unless blood or open wounds are present around the mouth. Hugging and other casual physical contact will not transmit HIV. Nor will sharing food or using the same toilet seat.1

What is the life cycle of HIV?

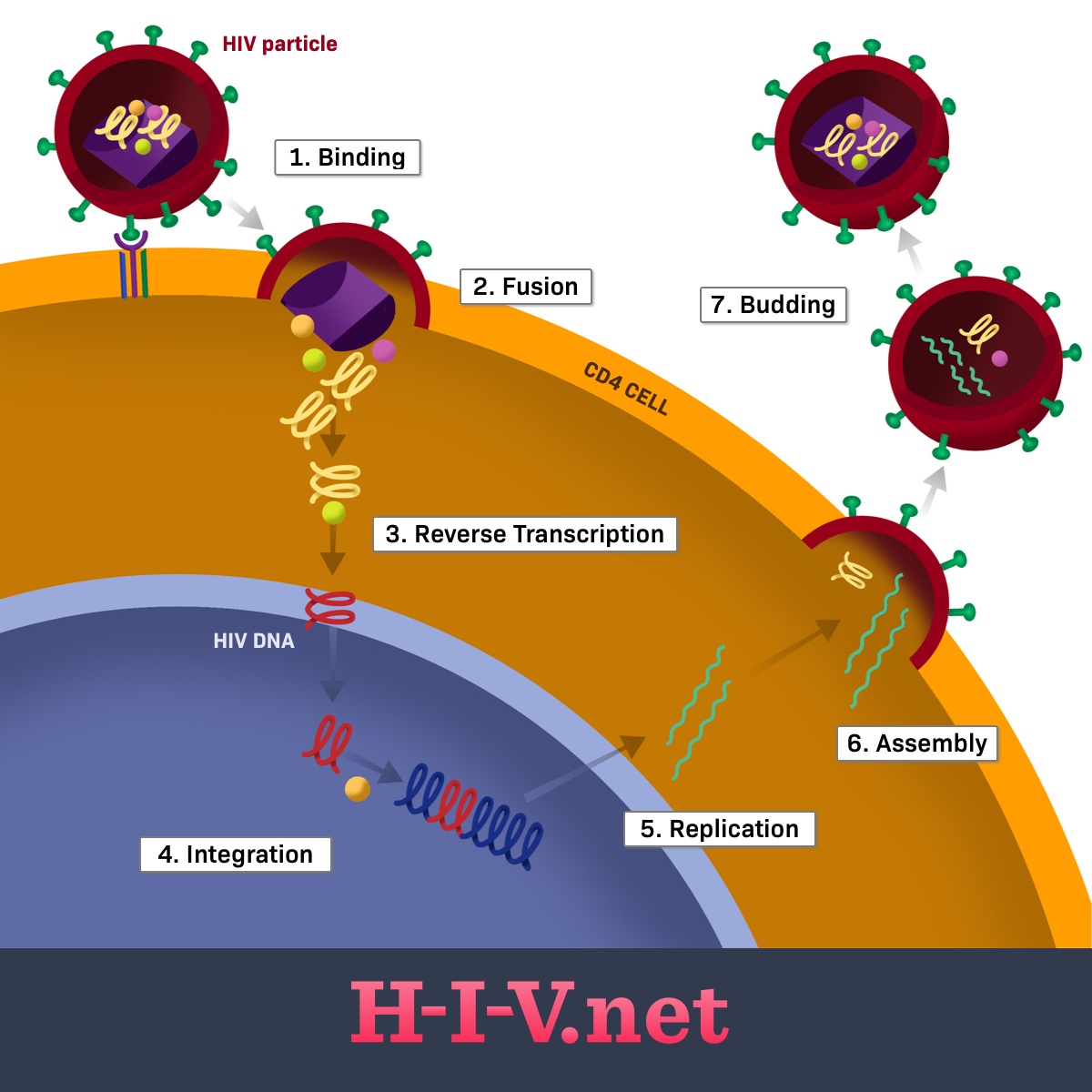

Viruses cannot replicate by themselves. They can only multiply by infecting host cells. HIV is transmitted into the body in the form of particles or virions. The virions must find and attach themselves to human cells to be able to survive. They do this through a series of steps (see Figure 1):2,4-6

- Binding

- Fusion

- Reverse transcription

- Integration

- Replication

- Assembly

- Budding

First, the HIV virion attaches or binds itself to the outside of a CD4 cell. The outer membranes of the 2 cells then fuse, allowing them to join. The HIV can now enter the CD4 cell.2,4-6

Once it is inside the CD4 cell, HIV releases an enzyme that converts the HIV’s RNA to DNA. This process (reverse transcription) lets the HIV DNA enter the nucleus of the CD4 cell. This allows the genetic material of both cells to combine (integrate).4-6

The virus can now use the cell’s own DNA to create more HIV proteins (replication). The proteins move to the outer edge of the cell, combine with HIV RNA (assembly), and are released as new virions (budding). The new virions find new CD4 cells to attach themselves to. The process then repeats, allowing the virus to spread through the body.4-6

When does HIV progress to AIDS?

Within a few weeks of exposure to HIV, a person will develop an acute level of infection. As the virus expands and spreads through the body, the person may have flu-like symptoms, such as headache or fever. The body’s immune system tries to fight the virus by producing antibodies. Antibodies are proteins the body uses to fight germs. The presence of these antibodies in the blood is how doctors can diagnose HIV infection.1,3

When a person reaches a chronic level of infection, symptoms often disappear. But the virus is still present, and the person can still transmit the virus to others.1,3

If a person’s CD4 count drops to below 200, they are diagnosed with AIDS. This is the most advanced state of HIV. By now the immune system is damaged to the point that infections are very hard to fight.1,3

The length of time from initial transmission to AIDS varies widely. It may take just a few years, or it may never happen. The sooner a diagnosis is made and a person begins treatment, the more easily HIV can be controlled.1,3

Controlling the progression

A combination of special medicines, called antiretroviral therapy (ART), can control the progression and transmission of HIV. ART blocks the various life stages of the virus and can stop it from spreading through the body. It can also reduce the risk of transmitting the virus to someone else.1,3,4

There is no cure for AIDS or HIV. But ART can help people with HIV live long, healthy lives.1,3,4